Luther and antisemitism: the floor to a Lutheran historian

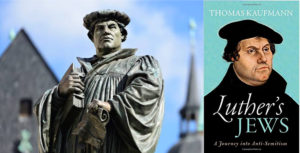

Few months ago, the Italian translation of the work Luther’s Jews by German historian Thomas Kaufmann was published by the publishing house Claudiana (219 pagine, € 19,50), with a foreward by Daniele Garrone. The text makes for a remarkable shortcoming of the Italian books panorama, by describing the relationship between the father of the Reformation, religion, and the Jewish people in an exhaustive and complete way.

Few months ago, the Italian translation of the work Luther’s Jews by German historian Thomas Kaufmann was published by the publishing house Claudiana (219 pagine, € 19,50), with a foreward by Daniele Garrone. The text makes for a remarkable shortcoming of the Italian books panorama, by describing the relationship between the father of the Reformation, religion, and the Jewish people in an exhaustive and complete way.

The thesis emerging from the study and exhaustively and convincingly argued may be summed up in an extremely simple and concise way: in the first writings Luther appears benevolent towards Jews, with the hope of their conversion; in the last writings, instead, Luther appears extremely aggressive and polemic, even with peaks of vulgarity and explicit invitations to violence, until going so far as to suggest governors persecute and expel the Jews.

The first Luther emerges with extreme clarity from the text Jesus Christ was a born a Jew (1523), written few years after the beginning of the Reformation (conventionally dated 1517). In the text Luther shows admiration and almost a sort of envy towards the Jewish people, the first interlocutor and recipient of the alliance with God, and towards the Hebrew language which contains and codifies this alliance. He made himself the spokesman for an unconditional religious tolerance towards the Jews, attitude which makes him positively stand out in his Century and in the preceeding ones. Luther’s hope is that his Reformation can eventually attract many Jews and push them to welcome the message and the figure of Jesus. Amongst the other things, he rejects the accusation (a current myth in the Middle Ages) according to which the Jews made ritual sacrifices of Christian children.

These considerations were variously recalled by the later Protestants and were stressed in particular by the Pietist movement and, in the contemporary age, by Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Protestant martyr against Nazism (La chiesa di fronte alla questione ebraica, 1933).

However, it is the thought of the second Luther – inequivocally and profoundly antisemitic, other than alien any evangelical and philanthropic perspective – that makes him stand out in a negative sense in the context of that day and that left an ill-fated aftermath in the following centuries until the Nazi shoah.

The writing The Jews and their lies (1543) is paradigmatic, just like his contemporary sermons and “table talks” (that is discussions and explanations which informally took place with his disciples after the meals), where the antisemitic hints appear with higher frequency and vehemence.

Some examples of the many possible hints (inverted commas are necessary). Commenting the evangelical episode of Malchus (name deriving from “king” in Hebrew), whose ear is cut off by Peter in an attempt to defend Jesus from the arrest, Luther sees in it an allegory of the Jewish people, who have been denied the earthly kingdom for their incapacity of listening to the word of salvation: “The kingdom was cut off the ear”. Again, commenting the (in his opinion) little consideration the Jews had of Jesus and Mary, which led them to the rejection of the Christian faith, Luther speaks about “lies”, “so impious and malicious lies”, which would show how they have been affected by “folly, blindness, and mental confusion”. And unlike the precedent writings, he restates the accusation according to which the Jews would have been guilty of the murders of Christian children.

In conclusion, even though “they must not be killed”, the antisemitic Luther invites governors to persecute and drive away the Jews. “Burn down their synagogues”, “force them to work, deal harshily with them, as Moses did in the wilderness, slaying three thousand lest the people should perish”. Jews had to be deprived of “all their books, all their prayer books, the Talmudic writings, and even the whole Bible”, without leaving “even one page” to them. Their houses had to be demolished, and they could be might be lodged “under a roof or in a barn”. Jewish religious practices had to be fobidden “under penalty of death”. They would not have been allowed anymore to exercise activities and functions as “lords, officials, or tradesmen”. They had to be deprived of “all cash and treasure of silver and gold”, that is what “they have stolen and robbed from us [through usuries]”. “Therefore, in any case, away with them!”, away in the territories of “the Turks and other pagans”, where, in his opinion, “these venomous serpents and little devils”, “children of the devil”, would not be able to harm the Christian people.

These very heavy and unfounded insults let us understand why a big part of historiography has seen a fil rouge between the second Luther’s antisemitism and the Nazi regime’s. As a paradigmatic example, the pamphlet by English scholar Wiener, titled “Martin Luther: Hitler’s Spiritual Ancestor” (1945), is mentioned, together with the defence of Nazi Julius Streicher during the Nuremberg trial, according to which Luther – not he – should have been made to sit in the dock.

The antisemitic Luther has thus been understandably overexposed by contemporary historiography with dozens of monographs and hundreds of articles, and the undeniable merit of Kaufmann’s book is the adequate contextualisation of the statements by the father of the Reformation. At the personal level, the death of Luther’s daughter threw him into a period of depression and pessimism which lasted until his death in 1546, period in which we find the heaviest antisemitic invectives. Moreover, Kaufmann specifies that Luther “criticised and demonised the Jews just as he did also to Papist Catholics and Turks”.

From the diachronic viewpoint, the scholar also highlights how anti-Judaism had been present for centuries at the popular and theological level and had bloody recrudescences during the fourteenth-century Great Plague, when throughout all Europe the Jews were superstitiously and falsely accused of being plague-spreaders.

4 October 2018

4 October 2018

Comments Feed for this article

Comments Feed for this article

Facebook comments