Does Alice Roberts Expose Christianity or Just Repeat Old Propaganda?

- News

- 18 Nov 2025

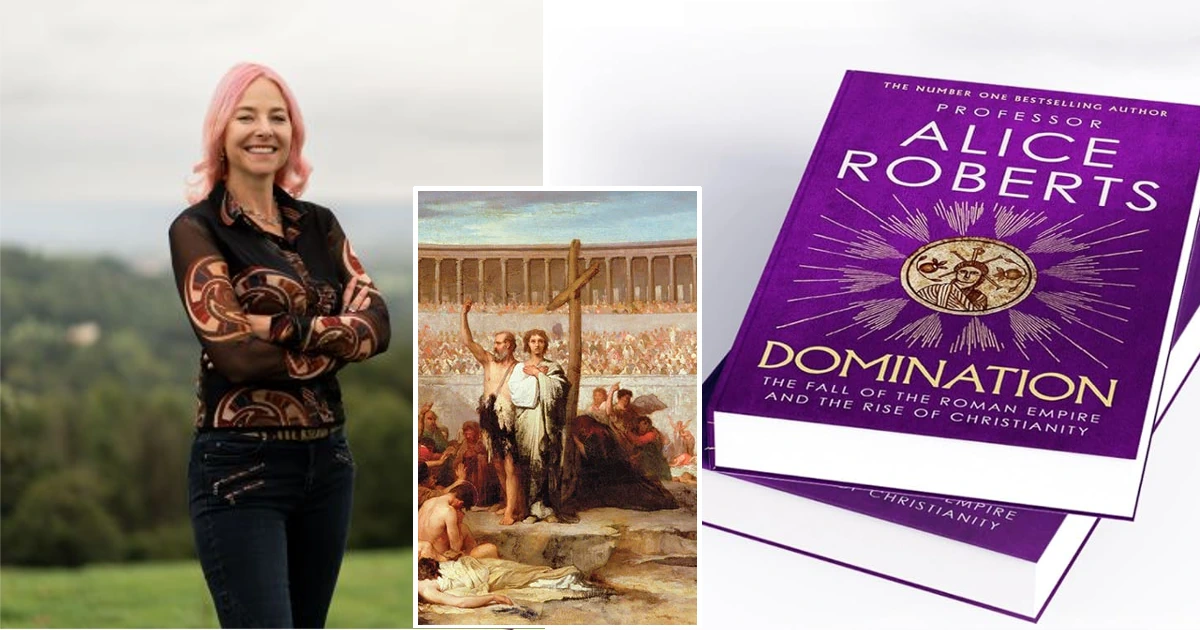

Review of the book “Domination” by Alice Roberts, a new attack on Christianity in the tradition of Edward Gibbon‘s anti-religious propaganda.

Christianity spread as a tool of domination and social control.

The most trivial and recycled thesis in human history is presented as “revolutionary” by Alice Roberts, an English writer and TV presenter and vice-president of the Humanist Society.

Who is Alice Roberts, the humanist presenter?

No specific academic title, but a PhD in paleopathology and a successful television career that has established her in the public imagination as a scientific communicator.

That is apparently enough to publish the book “Domination: The Fall of the Roman Empire and the Rise of Christianity” (Simon & Schuster 2025).

The most prominent positive review came from comedian Stephen Fry, who claims that this is a “first-rate historical thriller”.

The promise of hidden revelations and of discovering Christianity’s “true” nature deflates once we learn that her thesis is the usual stale claim: Christianity triumphed because it served the political elites, and its members were supposedly motivated mainly by the search for wealth and power.

Roberts clearly aims to respond to the bestseller “Dominion. The Making of the Western Mind” (Little 2020), written by professional historian Tom Holland, who argues that Western morality—rooted in universal human rights, charity, and care for the weak—seems natural or normal to us precisely because we swim in thoroughly Christian waters.

Attempts to deny Christian asceticism

The first half of the book is harmless and rather dull. The author summarizes, in a textbook manner, several pages of Wikipedia about the transition from Rome to the medieval world, with a lumpy prose that reveals Roberts’s amateur hand.

From that point on, Roberts goes on the attack, attempting to demonstrate the fundamental political, economic, and cultural motivations behind the rise, success, and dominance of Christianity in medieval Europe.

The first “myth” the author wants to debunk is that of Christian asceticism, the idea that early and medieval Christianity maintained a strong ideal and tradition of ascetic practices.

To deny this, Roberts selectively presents examples, including the monk Simeon Stylites, known for having lived 37 years atop a column to distance himself from the crowds of pilgrims who sought him out.

She mentions him likely only because she encountered him in a book by the anti-Christian forger Edward Gibbon, claiming that Simeon did this because “he clearly wanted his asceticism to be visible”1A. Roberts, “Domination: The Fall of the Roman Empire and the Rise of Christianity”, Simon & Schuster 2025, p. 39.

The argument does not improve when she applies the same method to Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, a bishop who chose to live in a stone cell on a small island.

Lo and behold, Roberts “discovers” that the island was actually “only one mile away” from the mainland, and that this supposedly “fake” ascetic maintained active social and noble networks. Shocking!

Following this pattern, the presenter is convinced she has proven that Christian asceticism was a “myth” and provides a final example: the Gallic bishop Eucherius of Lyon, another “cunning” figure who allegedly brought a large quantity of wine and cheese with him during a retreat!

Yet, if one checks the historical source she uses2I. Wood, “The Christian Economy in the Early Medieval West: Towards a Temple Society”, 2022, p. 53, it becomes clear that the list also included 2,000 kilograms of grain and 35 liters of oil, provisions meant for a community for 40 days.

Roberts fails to grasp that while wine and cheese today are artisan goods consumed by elites, in the 5th century they were considered basic food staples, just like grain and oil.

This does not show that Bishop Eucherius was a wealthy snob, but simply that he intended for his community to survive.

Did Christianity not have humble origins?

Another “myth” that Alice Roberts claims to dismantle is the idea that Christianity had humble origins and was a religion of the lower classes.

Her modus operandi is to select only evidence supporting her pre-established thesis, ignoring that most Christian leaders of the early centuries—Polycarp, Origen, Anthony, Martin of Tours—came from humble backgrounds, and that the Church was one of the most powerful engines of social mobility in the ancient world, comparable only to the Roman army.

Roberts, not being a historian, ignores that most converts in the cities were poor, and that it was urban masses who strengthened Christianity, as also seen in the conflict between the Bishop of Alexandria, Cyril, and the city prefect, Orestes, in the case of Hypatia.

“It is a staggering level of cynicism,” comments one reviewer. “And it produces a historical narrative that is both tediously flat and highly selective. It is so absurd as to be almost indescribable.”

The truth about Constantine’s conversion

Then we arrive at the classic theme of every epigone of Edward Gibbon: the conversion of Emperor Constantine.

A topic so complex that professional historians have devoted entire books to it, especially since there is no definitive evidence of what Constantine truly believed.

Alice Roberts, however, uses the episode to argue that the emperor adopted Christianity as a political maneuver, emphasizing whatever might disprove the sincerity of his conversion.

Yet she clearly fails to demonstrate what advantage Constantine would have gained from a “political” conversion to a tiny and persecuted religion.

British historian Peter Heather shows3P. Heather, “Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion”, Allen Lane 2022 that Christianity was not popular among the high aristocracy (in fact, they were among the last to convert, in the 5th–6th centuries), even writing that “at most, Christians amounted to no more than 1 or 2% of the total imperial population”4P. Heather, “Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion”, Allen Lane 2022, p. 22.

As Heather shows, Christianity was a political obstacle for Constantine, not an advantage. He became and remained emperor despite his conversion, not because of it.

Roberts portrays Constantine as Protestant anti-Catholic historiography has always done: as someone who politically steered Christianity, corrupting it into an institution based on power and wealth. As the aforementioned Tom Holland wrote, the anti-Christian polemic of the “New Atheists” is, to a large extent, simply old Protestant rhetoric with a fresh coat of paint.

Just a Story About Money

Another objective of Alice Roberts is to portray Christianity as a hoarder of wealth, from St. Paul (referring to a collection for the community of Jerusalem after the famine of the 40s AD) to anyone who lived in conditions other than poverty.

The “Church” is treated as a single, monolithic entity that exploited historical events to accumulate money, much like a Chiara Ferragni-style operation.

The problem is not that money was never accumulated, but rather the exaggeration that this was the norm — and especially the attempt to use contrary evidence as a way to reinforce the thesis.

The author, for example, mentions that Cyprian criticized the bishops of North Africa for having obtained wealth from moneylending and for neglecting their congregations, but she presents this reproach as merely superficial, since “it was problematic if Church officials appeared too greedy for money or focused on commercial interests” (p. 279).

Therefore, Cyprian did not sincerely believe such behavior to be wrong, according to her, but it was all just a matter of appearances.

Likewise, traditional Christian charity toward the poor is judged as inauthentic, rather “a profitable activity” (p. 147) and “a prolific business” (p. 259). Christian leaders, she claims, merely wanted the poor to remain poor as part of their “business model” (p. 262). All of it under a “religious cover” (p. 334).

These are barroom comments that are not even worth refuting.

Ignorant Anti-Religious Propaganda

Everything becomes clearer when one learns that on social media Alice Roberts shares (false) claims according to which Christmas and Easter supposedly derive from pre-Christian festivals.

Compared to her, the amateur Catherine Nixey whom we discussed last January becomes a shining authority on the history of Christianity.

Attempting to explain the “dominance” of Christianity solely through political power and money ignores the fact that, as masterfully explained by historian Philip Jenkins (Baylor University) in The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia – and How It Died (HarperOne, 2008), Christianity experienced enormous growth throughout the Asian continent during the very period “analyzed” by Alice Roberts, without imperial support, and without political or economic power.

When Franciscan friars visited the Mongol khans, they found Nestorian priests at their courts; and Portuguese missionaries discovered centuries-old Christian communities when they arrived in India. In the 9th century, while England had only two archbishops, the Syrian patriarch Timothy I presided over nineteen dioceses with 85 bishoprics.

Alice Roberts’ work is nothing more than a veiled and poorly documented polemic against Christianity. Just another one, lacking imagination.

The Editorial Staff

The latest news

- News

- 27 Nov 2025

0 commenti a Does Alice Roberts Expose Christianity or Just Repeat Old Propaganda?