The Virgin Mary Does Not Derive from the Goddess Isis

- Dossier

- 28 Jul 2025

The goddess Isis as a model for the Virgin Mary? That’s what mythicist religious comparativism claims when it deals with the figure of Mary. But several scholars have presented strong evidence against the alleged parallels between the Egyptian goddess Isis and Mary of Nazareth.

For centuries, the mythicist movement has tried to deny the historicity of Jesus by proposing bizarre parallels with a wide range of ancient mythological deities.

In recent decades, however, there has been a kind of surrender among proponents of religious comparativism targeting Jesus of Nazareth.

Their arguments have dried up, their theses remain unproven and unprovable, and scholars of Christian origins—regardless of their personal faith, including atheists—have published dozens of academic studies and popular books refuting them.

The eminent scholar Tryggve Mettinger (Lund University), at the conclusion of his comprehensive comparative study on pre-Christian deities and myths, decisively affirms the “uniqueness of Jesus of Nazareth in the history of religions”1T.N.D. Mettinger, The Riddle of Resurrection. Dying and Rising Gods in the Ancient Near East, Almqvist & Wiksell International 2001, pp. 220, 221.

The only remaining avenue for comparativists is to focus on parallels involving other Christian figures, especially Mary of Nazareth, the mother of Jesus.

THE VIRGIN MARY AND THE GODDESS ISIS: THE DOSSIER

- 2. MARY OF NAZARETH AND THE EGYPTIAN GODDESS ISIS

- 2.1 Iconographic parallels between Isis and the Virgin Mary

- 2.2 The Breastfeeding of Mary and Isis Is a False Parallel

- 2.3 “Virgo Lactans” is not the only ancient image

- 2.4 Chronological distance between Isis and Mary iconography

- 2.5 The Decline of Isis Iconography in the 4th Century

- 2.6 Few depictions of Mary nursing like Isis

- 2.7 Scholars reject the Isis–Mary parallel

—————————

1. RELIGIOUS COMPARATIVISM: WHO ARE THE MYTHICISTS?

So who exactly are the mythicists and the current proponents of religious comparativism between Mary of Nazareth and pagan mythological figures?

1.1 Alexander Hislop

No discussion would be complete without mentioning the anti-Catholic Presbyterian theologian Alexander Hislop, author of the 1857 bestseller The Two Babylons. His core thesis was that the Catholic Church is the product of a millennia-long conspiracy and a continuation of the pagan religion of ancient Babylon.

Needless to say, Hislop’s work is highly fanciful and devoid of any real historical or anthropological value.

Interestingly, after Hislop’s research was discredited by the academic community, one of his most enthusiastic contemporary supporters, evangelical pastor Ralph Woodrow, conducted his own research and concluded that Hislop’s book was deeply flawed and scandalously wrong.

He withdrew his book Babylon Mystery Religion (1966) from circulation and published The Babylon Connection? in 1997 instead.

In the latter work, Woodrow—still an evangelical—dedicated an entire chapter to debunking Hislop’s arguments about Mary of Nazareth2Woodrow R., The Babylon Connection?, Woodrow Evangelistic Association 1997, pp. 33–38, expressing regret that evangelicals have used such arguments to attack the Catholic Church’s relationship with Mary and apologizing for having once promoted these views.

Though still evangelical, Woodrow no longer associates the Catholic Church with paganism.

1.2 James George Frazer

In Italy, one of the few prominent figures of this niche mythicist current is anthropologist Marino Niola, who often appears in the media portraying Italy as essentially pagan and accusing Christianity of having “merely superimposed Christ, the Virgin, and the saints over the gods of Olympus”3Niola M., La Dea in esilio vestita da Madonna, Repubblica 08/2024.

As Niola himself admits4Niola M., La Dea in esilio vestita da Madonna, Repubblica 08/2024, these ideas are borrowed from Neoplatonic anthropologist James George Frazer and his work The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (1915). In it, Frazer applied Darwinism to cultural history, drawing extreme comparisons between wildly disparate elements—medieval texts, Indian rituals, and Scottish customs—often relying on second-hand sources.

Niola’s reliance on Frazer is a massive own goal, or perhaps he simply doesn’t realise that Frazer is still regarded as something of a laughingstock within anthropology.

As Fabio Dei, professor of Cultural Anthropology at the University of Pisa, aptly put it, the “thought” of James George Frazer must be “understood as ‘mythical,’ based more on analogical shortcuts than on clear and distinct concepts”5Dei F., Il mito in Frazer e nelle poetiche del modernismo, in Leghissa G. & Manera E., Filosofie del mito del Novecento, Carocci 2015, p. 79.

Dei further notes that Frazer’s writing is characterised by “a language and theoretical framework that are still nineteenth-century, unable to engage with contemporary academic debates, much less anthropological ones”6Dei F., Il mito in Frazer e nelle poetiche del modernismo, in Leghissa G. & Manera E., Filosofie del mito del Novecento, Carocci 2015, p. 79.

In his “crystal-clear nineteenth-century rationalism”, Frazer sought to “demonstrate the illusory nature of revealed religions and undermine the authenticity of Christianity, treating it as one of many late cults stemming from the archaic mythic-ritual complex”7Dei F., Il mito in Frazer e nelle poetiche del modernismo, in Leghissa G. & Manera E., Filosofie del mito del Novecento, Carocci 2015, p. 78. Yet even his contemporaries saw in Frazer’s grand-scale evolutionary and comparative framework “the embarrassing legacy of a prehistoric phase in the discipline”8Dei F., Il mito in Frazer e nelle poetiche del modernismo, in Leghissa G. & Manera E., Filosofie del mito del Novecento, Carocci 2015, p. 75.

Indeed, from the very beginning, Frazer’s work was criticised as “embarrassing” in academic circles. Anthropologist Godfrey Lienhardt confirmed that even during Frazer’s lifetime, his colleagues “largely distanced themselves from his theories and opinions”, and that his influence “occurred more in the literary world than in the academic one”9G. Lienhardt, Frazer’s anthropology: science and sensibility, Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 1993, pp. 1–12.

For readers interested in detailed critiques of Frazer’s The Golden Bough—the Bible of every contemporary mythicist—we recommend, among many, the studies of historian Timothy Larsen10Larsen T., “James George Frazer”, The Slain God: Anthropologists and the Christian Faith, Oxford University Press 2014 and David Chidester11Chidester D., Empire of Religion: Imperialism & Comparative Religion, University of Chicago Press 2014, who expose Frazer’s deception in applying Christian ideas, theology, and terminology from Western Europe to non-Christian cultures, with the aim of distorting those cultures to make them appear more Christian—thus enabling forced comparisons between pagan and Christian religious figures.

—————————

2. MARY OF NAZARETH AND THE EGYPTIAN GODDESS ISIS

The most common religious comparison involving Mary of Nazareth is with the Egyptian goddess Isis.

This notion is especially prevalent within Protestant circles, where it is believed that Isis served as the model for the Christian image of the Virgin Mary. According to those who accuse Catholics of syncretism, when pagan converts flooded the Church during the 4th century, they brought with them their cultural and religious practices.

This theory is so sweeping that it certainly includes some elements of truth (inculturation is a phenomenon that the Catholic Church finds not at all embarrassing and has openly discussed for a long time), but as it is commonly framed, it could be applied to virtually any aspect of Christian worship.

We should instead examine the matter in detail and analyze each individual element allegedly borrowed from paganism.

This dossier explores in depth the alleged assimilation of the cult of Isis into that of Mary of Nazareth.

It must be noted from the outset that those who argue for such assimilation, apart from a few shared epithets (“Mother of God” and “Queen of Heaven”), never provide any compelling parallels between the Christian veneration of Mary of Nazareth and the cult of Isis. Moreover, Isis and Mary were worshipped in entirely different ways: the former as a full-fledged goddess, the latter as significant primarily through her connection to her Son.

2.1 Iconographic Parallels between Isis and the Virgin Mary

Several scholars have focused on a visual similarity between Isis and Mary—an argument that does hold some weight and has led some to theorize a deliberate adoption of pagan worship practices by Christians.

The key connection identified lies in iconographic representations of Mary and Isis nursing their sons (Jesus and Horus). These are specifically known as: Virgo lactans (or “Nursing Madonna “ or “Madonna Lactans”) and Isis lactans (“Isis nursing”).

The archaeologist and priest Vincent Tran Tam Tinh was one of the foremost experts on Isis iconography and concluded as early as the 1970s that the only links between Mary of Nazareth and Isis are limited to these two types of images12Tran Tam Tinh V., Isis lactans. Corpus des monuments gréco-romains d’Isis allaitant Harpocrate, Brill 1973.

Tran Tam Tinh’s work has been recently revisited by archaeologist Sabrina Higgins in her comparative study of the Virgin Mary and the goddess Isis: “Tran Tam Tinh’s observation that iconographic similarities between Isis and Mary are confined to the ‘lactans’ type remains valid“13Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 76.

Other forms of iconographic depictions of Mary or Isis, outside the nursing motif, lack significant connections. The scope of comparative analysis is therefore greatly limited.

Comparativist authors essentially claim that Virgo lactans is a continuation of the artistic tradition of Isis lactans.

In his renowned study, Tran Tam Tinh offers a detailed analysis of the development of the iconography of the goddess Isis, tracing a rise in its popularity from around 700 BC. The similarities between “Isis lactans” and “Madonna lactans” are undeniable, and were acknowledged by Tran Tam Tinh himself.

2.2 The Breastfeeding of Mary and Isis Is a False Parallel

However, several scholars have raised numerous objections to the idea of a genuine parallel.

The first argument is that breastfeeding is simply a typical image of motherhood, common to all cultures around the world.

Both Isis and the Virgin Mary are depicted as women nursing their children—clear similarities can be drawn between them, but also with any other image of breastfeeding, ancient or modern, sculpted or painted.

Christians portrayed Mary of Nazareth holding the infant Jesus because that is presumably what she did when Jesus was a newborn, like any other mother in history. This does not make her a pagan goddess.

Renowned Egyptologist Françoise Dunand, professor emerita at the University of Strasbourg, emphasized that the image of a woman (or a goddess) holding a child is not unique to Isis and Mary of Nazareth, but appears frequently throughout history—in Greece, Anatolia, and even the Neolithic period14Dunand F., Isis: Mère des dieux, Errance 2000, p. 161.

2.3 Mary Breastfeeding Is Not the Only Ancient Image

There is a second argument, perhaps even more problematic for religious comparativists.

The iconography of the nursing Virgin Mary is not the oldest, or at any rate, it is contemporary with others in which the Mother of Jesus is represented in entirely different ways from the classic iconography of Isis.

Vincent Tran tam Tinh noted that the earliest depictions of the Virgin Mary primarily focused on Christological and eschatological themes, such as images of Jesus seated on Mary’s lap or being presented to the Magi15Tran Tam Tinh V., Isis lactans. Corpus des monuments gréco-romains d’Isis allaitant Harpocrate, Brill 1973, p. 43.

In these depictions, Mary plays a secondary role, reflecting what is written in the biblical accounts of Jesus’ birth.

Maria Giovanna Muzi, professor of Christian Iconography and Iconology at the Pontifical Gregorian University, indicated that the oldest Marian iconographic types are the historical cycles of the Infancy, such as the Annunciation, the Nativity, and the Adoration of the Shepherds and the Magi.

There are also independent images, such as the Mother and Child group (including Mary breastfeeding) and the Praying Virgin16Muzi M.G., L’iconografia absidale mariana della Chiesa indivisa quale Locus Theologicus, Theotokos XVI 2008, p. 26.

Among the oldest known artifacts, the Virgin Mother appears with and without the Child, in various distinctively Christian representations that align with the Gospel narratives.

In the Mother and Child group, the breastfeeding image appears only in some instances. In others, Mary is “cheek to cheek” with Jesus (known as the Virgin of Tenderness), or the Child is simply seated on her lap17Muzi M.G., L’iconografia absidale mariana della Chiesa indivisa quale Locus Theologicus, Theotokos XVI 2008, p. 47.

Anthropologist Tran tam Tinh also noted that the image of Jesus seated on Mary’s lap does not belong at all to the Virgo lactans iconographic type. The latter is characterized by Mary’s act of nursing her son—very different from depictions of a mother and child simply sitting together.

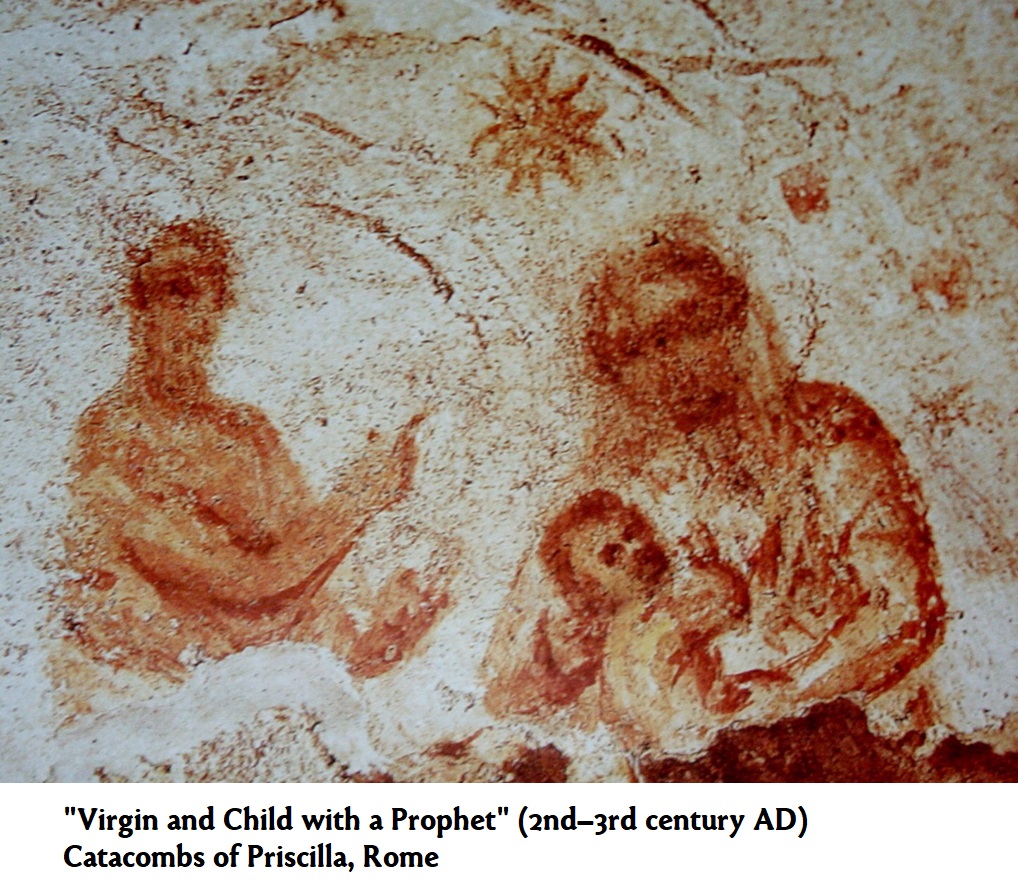

Currently, the oldest known images of the Virgin Mary are those found in the Catacombs of Priscilla in Rome, dating to the first half of the 3rd century (around AD 230–240). Below are the two depictions.

In one fresco, we presumably see Mary holding (presumably) the infant Jesus, though it is unclear whether she is breastfeeding him. The next paragraph delves into the details of this image.

Nearby is another image showing the Annunciation: Jesus is absent and the Virgin is shown seated, with a winged figure (the angel Gabriel) before her. The iconography is highly stylized and symbolic, typical of early Christian art.

In addition, there are other ancient representations of Mary in which breastfeeding is clearly absent.

For example, we refer to the Adoration of the Magi found on a sarcophagus housed in the Museo Pio Cristiano, dating to AD 330, and to those on a lunette of the arcosolium in the crypt of the Virgin Mary in the catacombs of Saints Peter and Marcellinus, as well as in the catacombs of Domitilla (first half of the 4th century).

Other early representational themes of the Virgin include the Nativity, such as that found on the sarcophagus of Boville Ernica (mid-4th century AD), where the Virgin is depicted meditating on the birth of her son.

2.4 Temporal Distance Between Iconography of Isis and That of Mary

There is a third key argument worth highlighting, concerning the temporal distance between the last image of the goddess Isis breastfeeding and the first depiction of the Virgin Mary performing the same act.

Indeed, there is disagreement among scholars as to whether the two earliest images claimed to represent the Virgin Mary nursing Jesus are actually depicting such a scene.

The first, already discussed in the previous paragraph, is the “Virgin and Child with a Prophet” discovered in the catacombs of Priscilla, dated to the late 2nd or early 3rd century.

Scholars seriously doubt that the Virgin is genuinely shown in the act of breastfeeding18Bonani B.P. & Baldassarre Bonani S., Maria lactans, Marianum 1995.

Archaeologist Sabrina Higgins writes, for instance, that “the child clutches at the woman’s breast, but there is nothing to indicate a breastfeeding scene.” She adds that “the painting lacks any attribute that could positively identify the woman as Mary.”19Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 73.

The second scene depicts the Good Shepherd at the centre, with the prophet Balaam to the right, seated beside the Virgin and Child. The child appears to stroke his mother’s breast, but again, Higgins notes, “there is no evidence to suggest breastfeeding.”20Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 73.

These two ancient images, found in the catacombs of Priscilla, do not clearly conform to the lactans type, and Tran Tam Tinh himself observed that they should not be considered representative of the earliest iconography of this kind.

Excluding these two early depictions, the first unmistakable and well-defined image of Virgo lactans appears in archaeological records only in the 7th century, and exclusively in Egypt21Tran Tam Tinh V., Isis lactans. Corpus des monuments gréco-romains d’Isis allaitant Harpocrate, Brill 1973, p. 42.

Specifically, they are two wall paintings discovered during excavations at the Monastery of Saint Jeremiah in Saqqara.

Likewise, no depictions of Isis lactans are known to exist after the 4th century AD.

This results in a significant and problematic gap of no less than 300 years between the last image of Isis lactans and the first of Nurising Madonna.

Such evidence led the eminent Vincent Tran Tam Tinh to conclude that any discussion of a direct chronological sequence between Isis and Mary of Nazareth in Egypt should be considered closed.

2.5 The Decline of Isis Iconography in the 4th Century

We now move on to the fourth argument against religious comparativism between the goddess Isis and Mary.

While there are various depictions of Isis breastfeeding in the 3rd century, only three survive from the 4th century (a limestone statue from Antinopolis, a wall painting at Karanis, and a limestone figurine from Akhmim22Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 74).

This clearly indicates a decline in the use of this type of depiction of Isis in the 4th century AD.

As already explained in the previous paragraph, the earliest uncontested iconographies of the Virgin breastfeeding appear three centuries after the last known image of the goddess Isis in such a pose—a representation already in marked decline.

This further weakens the possibility of any religious-cultural assimilation by Christians.

2.6 Few Images of Mary Nursing Like Isis

The fifth argument highlights the scarcity of Christian depictions of the Virgin Mary nursing. There are only seven such images.

All other iconographic representations of the Virgin Mary (the Adoration of the Magi, the Annunciation, etc.) bear no resemblance to Isis.

The iconographic strand of Virgo lactans is a recurring theme found almost exclusively in certain monasteries in Egypt23Muzi M.G., L’iconografia absidale mariana della Chiesa indivisa quale Locus Theologicus, Theotokos XVI 2008, p. 54.

The oldest depictions are wall paintings discovered in the Monastery of Saint Jeremiah in Saqqara, within the monks’ cells. These are visually distinct images: one shows no expression of affection from Mary toward Jesus, while the other is visibly more maternal in gesture24Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 75.

Still within the Monastery of Saint Jeremiah in Saqqara, a third image was reportedly present but is no longer visible25Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 75, as well as two others, also no longer visible, once located in the Monastery of Bawit26Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 75.

There are also two Virgo lactans images discovered outside a monastic context: one in the Church of the Red Monastery, near Sohag (dated to the 7th–8th century), and one found in 1996 in the Church of the Virgin Mary in the Monastery of the Syrians in Wadi El-Natrun (dated to the 7th century).

In total, therefore, among all types of depictions of the Virgin Mary, only seven images portray Mary nursing in a way similar to the goddess Isis (two found inside churches and five in monastic cells), moreover, 300 years after the last known representation of the Egyptian goddess.

Thus, even if one were to disregard the vast chronological gap and continue to argue that the iconography of the goddess Isis nursing strongly influenced that of the nursing Virgin Mary, such influence would be limited to just seven depictions.

2.7 Scholars Reject the Isis–Mary Parallel

The sixth and final argument we present is the position of the academic community that has analysed the alleged parallel between the Virgin Mary and the goddess Isis.

One of the most recent works is by archaeologist Sabrina Higgins, professor at Simon Fraser University and a specialist in the early cult of the Virgin Mary. At the end of her comparative study of Isis and Mary of Nazareth, she writes: “There is little evidence to suggest that this particular Isiac image had a profound impact on the artistic repertoire of the Virgin Mary”27Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 78.

Despite some obvious iconographic parallels, she adds, the image of the nursing Virgin Mary is “limited and confined to a monastic context and suggests that it was not widely adopted by those wishing to depict the Virgin”. Therefore, “it does not justify the conclusion that a deliberate adoption took place between the cults of Isis and Mary”28Higgins S., Divine Mothers: The Influence of Isis on the Virgin Mary in Egyptian Lactans-Iconography, Journal of the Canadian Society for Coptic Studies 2012, p. 78.

Averil Cameron, a leading scholar of Byzantine history at the University of Oxford, also wrote that religious development cannot be explained in monocausal terms, and that religious syncretism, if present in this case, played only a minor role29Cameron A., The Cult of the Virgin in Late Antiquity: Religious Development and Myth-Making, in Swanson R.N., The Church and Mary, Boydell and Brewer 2004, p. 1–21.

Clelia Martínez Maza, professor of Ancient History at the University of Malaga, instead firmly rejected any parallel or continuity between the two cults, observing that the figure of the Virgin Mary underwent a transformation from a minor character in Christian tradition to a divine presence starting with the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD. This places her entirely apart from Isis, who was wholly divine30Maza C.M., Los antecedentes isíacos del culto a María, Aegyptus 2000, pp. 195–214.

John McGuckin, a British theologian and professor of Church History at the University of Oxford, also rejects any syncretism, maintaining that depictions of Nurising Madonna, like others, were fully understood by Christians from the start within their own cultural system. In the case of nursing, he deems similarities with Isis to be incidental and insignificant31McGuckin J., The Early Cult of Mary and Inter-Religious Contexts in the Fifth Century Church, in The Origins of the Cult of the Virgin Mary, Burns and Oates 2008, pp. 1–22.

Two other scholars, Gail Paterson Corrington (Rhodes College) and Elizabeth S. Bolman (Case Western Reserve University), combining art history and theology, have noted that the meaning of the Virgo lactans image is strictly Christological, as it emphasises the divine nature of Christ.

Since Mary is a virgin, she would be unable to produce milk and would nourish Jesus with divine sustenance provided by God. The milk is thus interpreted as a metaphor for the Eucharist and retains an entirely Christian meaning, independent of any iconographic resemblance it may bear to Isis lactans32Corrington G.P., The Milk of Salvation: Redemption by the Mother in Late Antiquity and Early Christianity, Harvard Theological Review 1989, pp. 393–420 33Bolman E.S., The Coptic Galaktotrophousa Revisited, in Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium, Peeters 2004, pp. 1173–1184.

—————————

3. THE VIRGIN MARY DOES NOT DERIVE FROM MOTHER EARTH (OR THE GODDESS GAIA)

A fringe line of mythicism targeting Mary of Nazareth compares her to the Great Mother (or Mother Earth, or the goddess Gaia).

One such proponent is essayist Diego Conticello, author of an article lacking any bibliographical sources, in which he claims: “It is now historically proven that most of the devotional cults tied to the Virgin Mary in early Christianity derive directly or indirectly from the veneration of the Great Mother in some ancient civilisations”34Conticello D., Madonne Nere, un’eredità egiziana, La Provincia 02/10/2022.

So “proven” that the author deemed it unnecessary to cite any scholarly work in support.

In reality, these are theories found almost exclusively on online mythicist forums around the world, where the most commonly presented “evidence” is the similar epithet used for Mary: virgin and/or mother.

From this, parallels are drawn with the most bizarre deities, such as Semiramis, who embody values entirely contrary to Christianity and were worshipped in profane and dissolute cults.

3.1 The Opposing Cults of the Virgin Mary and Mother Earth

The goddess Gaia or Mother Earth and the Virgin Mary belong to two profoundly different religious and cultural worlds, and the latter represents everything that is the opposite of the Gospel message embodied by Mary of Nazareth.

While the Virgin Mary, venerated in the Christian tradition, is the mother of Jesus Christ—a human figure elevated to great spiritual significance for her obedience to God and her role as the conduit of the divine in Christ’s birth, a model of humility, purity and intercession—the goddess Gaia, in Greek mythology, is identified with the Earth itself, a primordial deity representing the creative and generative force of nature.

It is easy to verify that Gaia is not associated with any story of personal redemption or a specific relationship with an incarnate god, but rather embodies the cosmic principle that gives rise to all things, including the gods. She is worshipped as an immanent entity, Mother Earth, linked to fertility, nature and the cycles of life.

By contrast, Mary is venerated for her humanity transfigured by the divine, for being a mediator between God and humanity, and Marian devotion has always been imbued with Christological themes.

Where are the parallels between the two figures? They are each other’s opposites.

3.2 The Child of Mary and the Children of the Goddess Gaia (or Mother Earth)

The differences between Virgin Mary and Gaia become even more apparent when one considers that the children of Gaia (or Mother Earth), in Greek mythology, include every form of life, from titans to giants and other extraordinary beings.

Among Gaia’s most famous children are the Titans, born from her union with Uranus (the sky). For example, Cronus, the titan who overthrew his father to become king of the gods, and Rhea, mother of the Olympian gods.

Gaia also gave birth to the Giants, powerful and rebellious, who rose against the Olympian gods in the so-called Gigantomachy. She also bore the Cyclopes and the Hecatoncheires, beings with many arms and great strength, often associated with primordial chaos.

They symbolise powerful and destructive natural forces that often rebel against the cosmic order represented by the Olympian gods. They reflect the Greek myth of the constant struggle between chaos and order, primordial forces and divine balance, with Gaia as the mother of all, unable to fully control the power of her offspring.

3.3 The Iconography of the Goddess Gaia

There are no connections whatsoever from an iconographic standpoint either.

As explained by the Treccani Encyclopedia, in ancient art Gaia was typically depicted as a female figure emerging from the ground, often shown from the waist up (already in Greek art of the 5th century BC).

She was later portrayed lying on the ground, holding a cornucopia (a horn-shaped vessel filled with fruit and flowers) and accompanied by a young cow.

What possible comparison could there be, then, between all this and Christianity? What kind of connection could one possibly make between the cult of the goddess Mother Earth and the Virgin Mary, who is venerated solely because of her son, Jesus of Nazareth?

Aside from the common epithet “Mother”, neither the cult, nor the iconography, nor the “biography”, nor the values conveyed are in any way comparable.

—————————

4. CONCLUSION

The mythicist and comparativist theories that attempt to draw parallels between Mary of Nazareth and pagan deities like Isis or the goddess Gaia do not hold up under scrutiny.

After highlighting the methodological weaknesses and academic disrepute of mythicist authors such as Alexander Hislop and James Frazer, the dossier focused on the iconographic comparison between Mary and Isis, showing that the similarities in imagery related to nursing are superficial, rare, and historically far apart.

The undisputed images of “Virgo lactans” are few and appear later (or, at most, simultaneously) alongside many other types of Marian depictions; they emerge centuries after the last representations of “Isis lactans” and remain confined to Egyptian monastic contexts, without any diffusion into the universal Marian cult.

The comparison between Mary and Gaia is also dismantled, revealing profound differences in theological meaning, spiritual role, and iconography.

Even the evangelical pastor Ralph Woodrow, a former follower of mythicist Alexander Hislop, acknowledged that “every single Roman Catholic I have ever known considers Mary to be a woman of spotless character, a virgin, someone completely devoted to God and to virtue. None of these attributes fit any pagan goddess! Her lifestyle is exactly the opposite”35Woodrow R., The Babylon Connection?, Woodrow Evangelistic Association 1997 p. 35.

The veneration of Mary of Nazareth did not originate from the pagan worship of some primitive goddess, but from the early Christians who rejected paganism and would have never adopted or incorporated its cults.

The Editorial Staff

The latest news

- News

- 27 Nov 2025

0 commenti a The Virgin Mary Does Not Derive from the Goddess Isis